This report is the culmination of six months of in-depth research by The Afghan Times team inside Afghanistan. We interviewed hundreds of students, teachers, and education activists across the country to uncover the reality of the education crisis under Taliban rule.As the first light of dawn begins to illuminate the Afghan mountains, Fatima, a 10-year-old girl, wraps her scarf tightly around her head and shoulders, bracing against the chill of the early morning. Her younger brother, Bilal, just eight years old, struggles to keep pace as they begin their daily walk to school. Together, they travel along rocky paths that wind through the barren landscape, passing fields of parched earth and jagged hillsides. For nearly an hour, they walk in silence, their old, worn shoes kicking up dust in the cool air.

There is no school building waiting for them—only a wide, open field with a few scattered trees for shade. Their teacher, an older man named Hamid, sits on a stone, ready to greet them. Around him, other children, mostly boys, slowly gather, settling on the ground. Fatima is one of the few girls who dares to attend, but she knows her time is running out. In just a year, she will be forced to stop, as the Taliban only allow girls to study until the sixth grade.

“When I am here, I feel free,” Fatima says, her voice steady despite the hardships she faces. “I forget that one day, I might have to stop coming. For now, I just want to learn as much as I can.” Her eyes, bright and determined, stand in stark contrast to the dry, dusty land that surrounds her—a landscape as challenging and resilient as the children who live within it.

A Forbidden Future – The Struggles of Afghan Girls

For Fatima and thousands of other Afghan girls, education is not a guarantee but a fragile dream, one that could shatter at any moment. Since the Taliban regained control in August 2021, girls have been allowed to study only up to grade six. For those who have tasted the freedom of education, being forced to stop is a heartbreaking and confusing reality.

Eleven-year-old Aisha still remembers the day she learned she would no longer be allowed to go to school. “I was in the middle of a lesson,” she recalls, her voice barely above a whisper. “Our teacher told us we had to go home and that we might not come back. I cried the whole way home, holding my books because I didn’t want to let them go.”

Aisha’s family, like many others, believes in the importance of education, but they are too afraid to defy the Taliban’s orders. Now, Aisha helps her mother with household chores and cares for her younger siblings. “I read when I can, using my old books,” she says. “But it’s not the same. I feel like I am falling behind.”

The Long Walk for Knowledge – Girls Crossing Villages for School

It is not only the boys who make long treks for education; many Afghan girls under 11 also undertake dangerous and exhausting journeys between villages just to attend school. With limited educational facilities available, some girls walk hours each day, often risking their safety and defying cultural expectations, just to sit in a classroom.

Ten-year-old Layla wakes at 4:30 each morning to begin her journey. She walks alongside her cousin, Mariam, from their small village to a neighboring one where an open-air class is held. The girls cover their heads and faces with scarves, not just for modesty, but to shield themselves from the dust and to avoid unwanted attention from passersby.

“We walk quickly, and we never stop, even when we’re tired,” Layla says, describing how they rush to arrive before the teacher begins his lessons. “It is not safe for us to be out alone, so we stay together and watch for each other.” Sometimes, they arrive just as the sun begins to rise, the sky shifting from a deep purple to a bright orange.

Mariam, who dreams of becoming a doctor, knows the journey is dangerous. “We see boys playing in the fields, but we can’t stop,” she says. “Some people tell us we should be at home, not in school. But I tell them, ‘This is my chance to learn. Don’t take it from me.’”

Their determination is fierce, but they know their days in school are limited. For now, they keep walking, each step a defiance of the barriers placed in front of them.

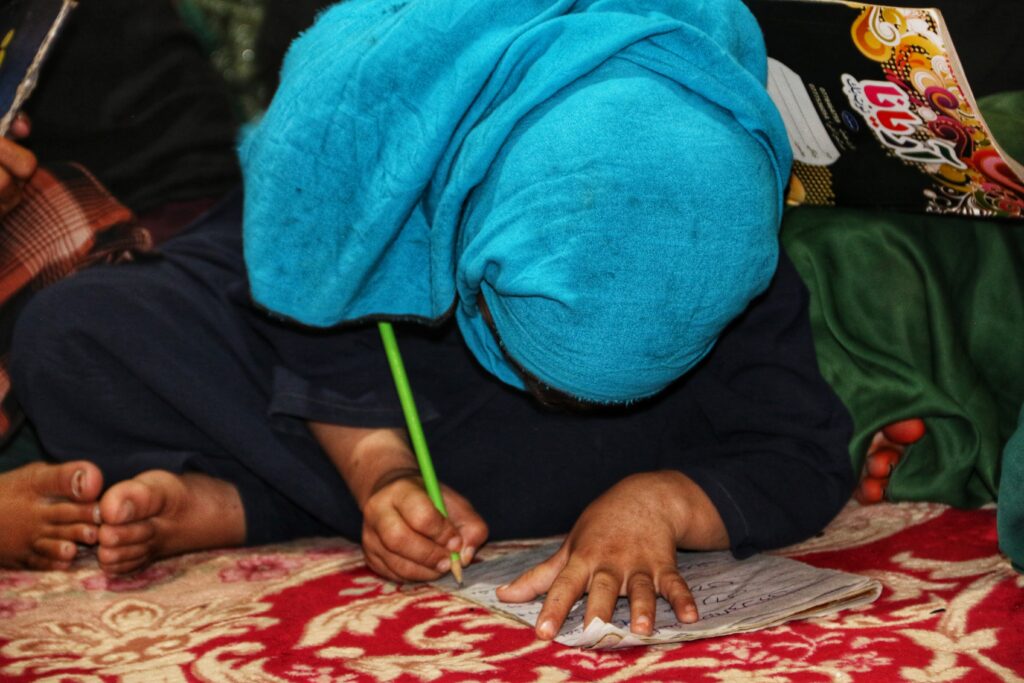

Learning Under the Open Sky – Classrooms Without Walls

The lack of school buildings in rural Afghanistan has forced many communities to adapt. Across the country, thousands of children attend makeshift classes without roofs or walls, often exposed to the elements. In the summer, they face the searing heat, and in the winter, they endure biting winds and frigid temperatures. Yet, they come.

“Sometimes, the wind blows our papers away, and we have to chase them,” says Zabiullah, a nine-year-old boy whose school is nothing more than a clearing under an ancient walnut tree. “In the winter, our teacher lights a small fire, and we take turns warming our hands. We sit close together so we can hear him over the wind.”

Despite the challenges, Zabiullah’s face lights up when he talks about his favorite subject—math. “I like numbers,” he says with a shy smile. “They make sense to me, even when the world does not.”

For children like Zabiullah, these open-air classrooms are both a blessing and a limitation. They offer a space for learning, but the lack of proper facilities—desks, chairs, blackboards—hampers the quality of education they receive.

The Toll of Economic Hardship – Choosing Between School and Work

In many Afghan families, poverty dictates the choices children must make. With the country’s economy in a dire state, children are often forced to abandon their education to support their families. This is especially true for boys, who are seen as breadwinners from a young age. The need for income pushes them into labor—whether it’s in fields, workshops, or markets—leaving little room for school.

Twelve-year-old Farhad works in a car repair shop six days a week. His hands, though small, are calloused and stained with oil. After school each morning, he heads to the shop where he spends hours fixing tires and engines. “I like school, but I have to help my father,” he says. “If I don’t work, we won’t have enough to eat.”

His teacher, Mr. Jamal, understands the pressure many of his students face. “I try to make my lessons practical,” he explains. “I teach them things that will help them in the future—basic math, reading, how to understand a calendar. They need skills they can use in their work.”

For Farhad and others like him, school is a luxury, and every lesson learned is a small victory against the harsh economic realities they face.

A Childhood Interrupted – Girls’ Secret Schools and Hidden Learning

Despite the Taliban’s restrictions, some Afghan girls continue to study in secret. In cities and towns, underground networks of female teachers have emerged, teaching girls behind closed doors, in basements, and in hidden corners of homes. These secret schools are often small, with only a handful of students, and operate with the constant threat of discovery.

Eight-year-old Maryam attends one such secret school. Every few days, she slips out of her house before dawn and makes her way to a neighbor’s house, where a former teacher, Mrs. Khalida, holds classes for a small group of girls. “We have to be very quiet,” Maryam says, her voice trembling. “Sometimes, we hear people outside, and we stop. We pretend to play if someone knocks on the door.”

Mrs. Khalida, a former university lecturer, knows the risk she is taking. “I cannot just sit back and watch these girls be denied their future,” she says. “They have a right to learn, even if the world has forgotten them.”

These hidden classrooms are lifelines for Afghan girls, but they are not enough. Without proper support, the education they receive is patchy and incomplete. Yet, for Maryam and her classmates, it is a chance to dream.

The Unseen Teachers – Courage Amidst Chaos

Afghanistan’s teachers are among the most unsung heroes in this educational crisis. Many have not been paid in months, yet they continue to teach, driven by a profound sense of responsibility. In rural areas, teachers are often community members who have some level of education—sometimes just a high school diploma or a few years of college—and who feel compelled to pass on what they know.

Abdul, a teacher in a small village school, gathers his students under a large mulberry tree each morning. He receives no salary, only small donations of food from grateful parents who value his dedication. “I teach because someone once taught me,” he says. “Knowledge should not stop with me. It must continue, no matter the cost.”

His students—boys and girls alike—listen with rapt attention as he explains basic science, using whatever he can find: rocks, sticks, leaves. His classroom may be unconventional, but for his students, it is a window to a world they might never otherwise see.

A Forced Transition – When Girls Are Married Off at 11

In many parts of Afghanistan, when girls reach the age of 11, their education is abruptly halted—not because of academic failure, but because of societal expectations. The tradition of early marriage often means the end of a girl’s educational aspirations.

Ten-year-old Laila was one of the brightest students in her class. Her teacher, a man named Zahir, remembers how she would ask insightful questions and

help others with their homework. But shortly after she turned 11, her life took a different turn. Laila’s father, pressured by family and societal norms, arranged for her to marry a man three times her age.

“I didn’t understand why I had to stop going to school,” Laila says in a quiet voice. “I wanted to be a doctor, but my father told me it was time to grow up.”

Her marriage ceremony was a small, quiet event in their village, attended by relatives and neighbors. Laila, dressed in a red dress, smiled nervously, knowing she was expected to be a wife rather than a student. Now, at just 12 years old, Laila is confined to her home, caring for her husband’s children from a previous marriage.

“I still dream of being a doctor,” Laila says wistfully. “But I don’t think I will ever get the chance.”

Finding a Way – A Girl Who Works to Make Carpets

While many girls face early marriages, some find other ways to continue contributing to their families without giving up on their dreams. Mariam, at 13 years old, has found an unexpected opportunity to keep learning and earning.

Mariam’s family is poor, and she knew she had to help. She learned how to weave carpets from her grandmother and now spends hours each day in a small room at the back of their home, weaving intricate patterns. Her hands, though young, are steady, and she has already made a name for herself in the local market.

“I don’t want to marry yet,” she says firmly. “I want to work, learn, and one day, I hope to open my own carpet business. Education is still important, and even though I can’t go to school, I can teach myself.”

Mariam uses her earnings to help her family pay for food and basic necessities. Although her opportunities are limited, she finds pride in her work, and through her determination, she has kept the door to education slightly ajar.

A Nation Without Education – The Crisis of Afghan Students

Afghanistan’s education system has been in turmoil for decades, and the situation has worsened under the Taliban’s rule. According to the United Nations, more than 3.5 million children in Afghanistan are currently out of school, with girls disproportionately affected. The 2021 Taliban takeover closed educational doors to many girls and women, exacerbating an already fragile education system.

The World Bank reports that only 37% of Afghan children aged 6 to 14 were attending school in 2020, with this number dropping significantly for girls after the Taliban’s return to power. Even before the Taliban’s ban, many children, particularly in rural areas, lacked access to school buildings, teachers, and educational resources.

“Access to education has always been a challenge in Afghanistan, but since the Taliban returned to power, the situation has become dire,” says Abdul Samad, a former Afghan educator. “Many children are not only out of school but are now forced into labor or early marriages, depriving them of any chance to build a better future.”

The future of Afghanistan’s children remains uncertain, and with every passing day, the number of children deprived of education grows.